I ran across

this today, and thought I'd share. This young woman, Andrea Palpant Dilley, has a story with some similarities to mine: raised in rather traditional church settings; at some point (for me it was in my late teens) we opted for a more "hip" and "informal" Christianity, but then later found ourselves attracted to a rich and deeply liturgical spirituality.

I recently told some young clergy friends that leaders in my own denomination seem to have lost confidence that our traditional ways being church can "work" anymore, so everyone is talking about what and how to change. Yet the irony is that our traditional ways of being church are precisely what brought us (the young clergy) to faith in Christ, it is precisely what has in fact "worked" for us, and maybe our loss of confidence is a bit overblown, maybe we need to be more specific in our assessments than "the old ways don't work." I think some old ways (especially at the denominational level of costly boards and agencies with little connection to the local church, or overly politicized methods of making decisions and of choosing bishops) do need to go; but there are other (and far more ancient) traditions that we need to hang onto as well.

In a time when churches seem to be frantically grasping at "whatever change will work," Andrea cautions us to change wisely and not to look only at the short-term; here is what she writes:

-----------------------------------

When I came back to church after a faith crisis in my early 20s, the

first one I attended regularly was a place called Praxis. It was the

kind of church where the young, hip pastor hoisted an infant into

his arms and said with sincerity, “Dude, I baptize you in the name of

the Father, Son and Holy Spirit.”

The entire service had an air of informality. We sat in folding

chairs, sang rock-anthem praise and took clergy-free, buffet-style

communion. Once a month, the pastor would point to a table at the

back of the open-rafter sanctuary and invite us to “serve ourselves” if

we felt so compelled.

For two years, my husband and I attended Praxis while he did graduate

work at Arizona State University and I worked as a documentary

producer. As someone who had defected from the church at age 23, I

thought it was the perfect place for me: a young, urban church located

four blocks from Casey Moore’s Irish Pub, an unchurchy church with a

mix of sacred tradition and secular trend.

I’m not the first person ever to go low-church, and Praxis isn’t the

first institution to pursue that hard-to-get demographic: young people.

Across America today, thousands of clergy and congregations -- even

entire denominations -- are running scared, desperately trying to

convince their youth that faith and church are culturally relevant,

forward-looking and alive.

For some, the instinct is to radically alter the old model: out with

the organ, in with the Fender. But as someone who left the mainstream

church and

eventually returned,

I’d like to offer a word of advice to those who are so inclined: Don’t.

Or at least proceed with caution. Change carefully; change wisely,

with thoughtfulness and deliberation. What young people say we want in

our 20s is not necessarily what we want 10 years later.

Churches, of course, are right to worry. They’ve been losing young people like me for years.

A study released

last fall by the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life found that

not just liberal mainline Protestants but also more conservative

evangelical and “born-again” Protestants are abandoning their

religious attachments. Our complaints against the church know no bounds:

We don’t like the politics. We want authenticity and openness. We

demand a particular worship aesthetic.

Churches often leap to meet these demands, and yet the arc of my own

story suggests that chasing after the most recent trend may not be the

answer. As

I’ve written elsewhere,

I was raised in a small Presbyterian congregation but left and

later returned to the church for reasons too complex to summarize here.

When I slipped back in, I wanted what my own parents had wanted in

their hippie youth back in the 1970s: an anti-institutional church that

looked less like a church and more like a coffee house. But after

two years at Praxis, the coffee tasted thin.

I felt homeless in heart. I missed intergenerational community. I

missed hymns and historicity, sacraments and old aesthetics. I missed

the rich polity -- even the irritation -- of Presbytery.

In 2007, when my husband and I moved from Arizona to Austin, Texas,

and went in search of a church, we skipped the nondenominationals and

went straight to the traditionals.

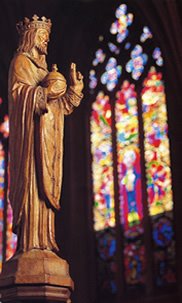

We found an

Anglican church where every Sunday morning we now watch clergy process

up the aisle wearing white vestments and carrying a 6-foot cross.

We take communion from an ordained priest who holds a chalice of

blood-red wine and lays a hand of blessing on our children. We sing the

Lord’s Prayer and recite from the Book of Common Prayer -- in which

not once in 1,001 pages does the word “dude” ever appear.

In my 20s, liturgy seemed rote, but now in my 30s, it reminds me that

I’m part of an institution much larger and older than myself. As the

poet Czeslaw Milosz said, “The sacred exists and is stronger than

all our rebellions.”

Both my doubt and my faith, and even my ongoing frustrations with the

church itself, are part of a tradition that started before I was born

and will continue after I die. I rest in the assurance that I have

something to lean against, something to resist and, more importantly,

something that resists me.

Labels: Ancient-Future Worship, church renewal, Sacraments, Spirituality and Liturgy